At 9.30 PM on July 21, 2025, a seismic event took place that left the nation’s political crowd pretty mystified. The Vice President of India, Jagdeep Dhankhar, had driven to Rashtrapati Bhavan, carrying in his pocket his letter of resignation, citing reasons of health for stepping down with two years still left in his term.

The Dhankhar earthquake not only exposed the precarious sanctity of a high constitutional office, it also shook many assumptions about the seductive notion that all was honky-dory in the Narendra Modi command and control tent.

As it happened, Vice President Dhankhar can claim the dubious honour of being the first man to be fired from the second-highest constitutional office in the land.

A bad day for the republic.

A very bad day for political journalism in India.

Till 9.28 PM, when Dhankhar himself put out his letter of resignation on Twitter, not a single reporter in the national capital (or outside) had any inkling that relations between the Vice President and the Prime Minister had deteriorated to such an extent that the extreme most precipitous measure had to be resorted to.

And, this in a town where reporters, anchors, bloggers and podcasters pretend to be privy to the inside track on what is cooking atop Raisina Hill; there was stunned silence in newsrooms and studios. Of course, with the alacrity of a professional pickpocket the political reporters were soon churning out reasons for why Dhankhar had to be given the boot.

The office of the Vice President, under the Constitution of India, is essentially a ceremonial office—but he acquires a consequential role when he presides over the Rajya Sabha. The Prime Minister and the Council of Ministers depend upon the two presiding officers—the Speaker of the Lok Sabha and the Chairman of the Rajya Sabha—to manage their respective houses and to help the executive navigate its legislative agenda and assert its parliamentary control. But no “lobby correspondent” was able to discern that something was amiss between Dhankhar, the Chairman, and the government’s parliamentary managers. It was a moment of collective blackout for political journalism in India.

What should be a matter of professional embarrassment is that no political correspondent has yet revealed how the process of giving the boot took place. After all, the Vice President of India is not an ordinary office; he is not anyone’s employee; his is an elected post. He is not like a housemaid who can be told not to come back from the next day just because she had broken a valued piece of expensive crockery. We are not a banana republic. And, how could the Vice President simply put in his papers? A drama worthy of Mario Puzo. Yet, the political reporter remains clueless.

Political journalism, always deemed the most prestigious slot in any news organisation, has been losing its mojo for some time now. Take, for example, this business of “electing” a new president of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). No political journalist has so far gathered the professional courage to put her/his byline on a story authoritatively telling the reader the identity of the potential successor to J. P. Nadda. And, the sense of self confidence is so total and complete that no editor dares demand of her political bureau what was holding up the “election” of a new president in a party that claims to be the largest in the country.

The political journalist has been robbed the very agency of questioning the highest political authority in the land.

Admittedly, many structural changes that have come into effect since 2014 have proven deleterious to the practitioners of political journalism. Since 2014, the most fundamental—and, the most consequential—change has been that the political reporter has been denied access to the Prime Minister.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi has the distinction of not having had a formal press conference in India with the media all these years. He has also discontinued the earlier established practice of the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) inviting news organisations to nominate their correspondents/representatives/cameramen who would travel in the prime minister’s plane on his overseas visits.

A few days together would invariably offer opportunities for the accompanying press to have sometimes structured, sometimes unstructured interactions with the prime minister. It was understood that both the prime minister and the media benefitted from such encounters—the prime minister and his aides were able to explain the rationale and the thinking behind policy positions or political developments; the reporters got a chance to see up-close the top political boss at work.

The cumulative effect of the systematic denial has been devastating. The political journalist has been robbed of the very agency of questioning the highest political authority in the land.

The Prime Minister’s press conferences used to be an occasion for showcasing a vibrant media at work. There was an unspoken, but much felt sense of competition among media peers to think cleverly and imaginatively about how to pin down the prime minister on this or that specific issue. In the good old days, every political reporter carried a chip on her shoulder. How to interpret and analyse the interaction was in itself an acquired competence. A kind of Rashomon effect would kick in.

Then, the Central Hall in Parliament House was kind of decommissioned. The Central Hall in the old Parliament building was an institution, with its own informal rules of interaction between “lobby” journalists and parliamentarians, cutting across party lines. Access to the Central Hall itself was limited to senior journalists; there was a sense of selectiveness with its own burden of responsibility. It was a neutral ground where politicians and journalists would exchange gossip, rumours, assessments, and a few clues, enough to enable a sharp journalist mind to pick up the scent of something significant brewing. L. K. Advani, Sushma Swaraj, Arun Jaitley from the BJP, and the likes of Ahmed Patel, Janardan Dwivedi, Murli Deora, and sometimes even Sonia Gandhi would come to the Central Hall and hold a “durbar”.

Perhaps the death of Jaitley also hastened the demise of political journalism. Jaitley had built up a formidable political persona for himself by being accessible to journalists—he was a valued source for rampant intrigue, infighting, factionalism, first, within the BJP and later in the Vajpayee government. As the Leader of Opposition in the Rajya Sabha during the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) days, he was deadly effective in planting stories against the Congress and the Manmohan Singh government with (willingly) gullible political journalists over cups of coffee in the Central Hall.

All that changed in 2014. The Prime Minister and his cabinet colleagues have kept journalists at arm’s length. The internal message was that the political journalist was to be disabused of any sense of institutional entitlement. If the journalist was to be given any access, it would have to be on “our” terms and at our convenience. After over a decade of relentless control and manipulated access, the political journalist is on bended knee and has completely internalised his assigned role as a cheerleader. He has lost his touch, his craft, that analytical prescience that enabled him to discern patterns where others could see only confusion and chaos. He finds himself stranded on a no-information, no-access island when a Dhankhar denouement takes place.

The message has been quite clear: the media is not needed—except as an obedient and useful megaphone. The new modus operandi is to put out a few lines on twitter or Facebook, sending the political reporter on a wild goose chase. It is a one-way traffic of information. And, the establishment has also developed a mechanism of creating “information cells” which issue “advisories” on how a political development should be reported and analysed.

In the good old days, the political journalist was the conduit for friends and foes in the public arena to talk to each other; send out signals of intent to factional rivals; or, sometimes even to overseas stakeholders. Occasionally, a story would send tremors through the ruling regime of the day. No such possibility is permitted in Naya Bharat.

We have a new breed of politicians which feels that it is more rooted and knows the pulse of the masses better than the political reporter in Delhi or even in Jaipur or Patna. In addition, the new politician is armed with technological heft and a political toolkit to manipulate the “pulse” of the people and the mood of the nation. The very institution of political journalism stands diminished.

(Views expressed are personal)

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Harish Khare is a Delhi-based senior journalist and public commentator.

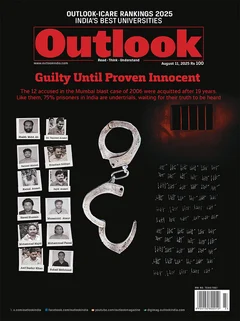

온라인 카지노 사이트 Magazine’s next issue, “Guilty Until Proven Innocent”, looks at the 19 years lost of those who were in jail and those who thought justice was served, until it wasn’t. This article appears as 'Unmourned Death Of Political Journalism' in the magazine.