Inside a multi-storey tenement block in Srinagar, Kashmir, rice boils in a pot on a gas stove set against a coarse wall that speaks poverty in any language—Hindi, Urdu, Dogri, Kashmiri—while Muzamil Ansari, a 25-year-old from Uttar Pradesh, pushes the foot pedal of a sewing machine in the small room he shares with three other Hindi-speakers, all from his native state.

As low-paid house painters and tailors who need to send money to their families back home, this cramped space is the best they could afford in the Valley where they are easily distinguished from the locals due to the language they speak and their relatively browner skin tone.

Since 2019—the year Muzamil came to Kashmir to look for work as a tailor as “there were almost no jobs for us in UP”, and also the year the Narendra Modi government in New Delhi abrogated Article 370 of the Constitution of India that had granted Jammu and Kashmir a nominal and progressively denuded form of autonomy—migrants like him have found themselves in the midst of an altered political landscape where they are often identified as a “demographic threat”, as “outsiders” likely to grab jobs and land from the local residents.

“The fear that people like us would deprive Kashmiris of their jobs has no basis,” says Muzamil as his roommates nod in agreement. “I never went to school, so I am ineligible for any government job and earn only Rs 500-600 a day. I barely save enough to send home, how could I possibly buy land to settle down in Kashmir?” The widespread fear persists nonetheless and extends also to recent rows over the use of official languages, which pit not just locals against non-locals, but also the people of Jammu against the people of Kashmir.

When the BJP demanded the cancellation of a notification issued by the J&K Services Selection Board (JKSSB) for filling up posts of naib tehsildars in the revenue department, claiming the long-time practice of making the knowledge of Urdu mandatory keeps out Dogri-speaking aspirants, the saffron party brought into the open alleged fissures between the overwhelmingly Muslim Kashmiri-speaking people of the Valley and the mostly Hindu Dogri-speaking people of Jammu. Following several days of BJP-led protest marches in Jammu, the Central Administrative Tribunal directed that the JKSSB advertisement be put on hold. Chief Minister Omar Abdullah, however, reiterated that candidates needed a basic knowledge of Urdu to do the job as the revenue records were in Urdu. “Even earlier, officers of the Jammu and Kashmir Administrative Service (JKAS) and the 온라인카지노 Administrative Service (IAS) who didn’t know Urdu were given time to learn it,” the CM added.

Prominent Urdu writer Mirza Mohammed Zaman Azurdah says the JKAS and IAS officers were trained in Urdu as “much of the official work was done in this language”. “In Kashmir the revenue records have always been in Urdu, and there is a good use of Persian terminology, too,” he says. Writer and activist Abdul Rashid Hanjura, who works for the promotion of Urdu, agrees. Dismissing the controversy as an attempt to “score political points”, Hanjura points out that the police and revenue departments in J&K cannot function without the language. “The police reports are prepared in Urdu, as are the revenue documents of land. We can’t do this in Hindi,” he says.

According to Kashmiri linguist Nazir Ahmad Dhar, Urdu has been an official language since the reign of the Dogra dynasty as people from different regions in the erstwhile princely state could speak the language. “Urdu was introduced as an official language by the Dogra rulers so the people from different regions such as Jammu and Ladakh could communicate with each other in a common language,” he says. “If any other language had been made the official language, then one or the other group would have protested against the move. English, too, became a supporting language as all the scientific material is written in that language, making it necessary even for academics.”

Pointing out that languages have become richer through interactions among people speaking different tongues, Dhar says the Kashmiri language has even borrowed words from English such as “crackdown” and “militant”, which are now in common use. “Languages have grown through diverse use and interactions among people who speak differently,” he adds.

Even as the demand for a separate state for Dogri-speaking people gains a foothold in the BJP-dominated Jammu region, leaders in Ladakh have sought a separate state for people speaking various Tibetic languages.

Similarly claiming that languages “thrive through cultural exchange”, Azurdah rejects the idea of associating any language with a particular religion. “So many Hindus have contributed to the enrichment of Urdu and so many Muslims have enriched the Hindi language through their work,” he says. In September 2020, both Houses of Parliament passed the Jammu and Kashmir Official Languages Bill, adding Kashmiri, Dogri and Hindi to the list that had until then comprised only Urdu and English. “I think Hindi has been made an official language to enable migrants from states like UP to read and write documents,” says Azurdah.

Since the abrogation of Article 370 and bifurcation of the erstwhile ‘special status’ state into two Union territories—J&K and Ladakh—political parties in Kashmir have opposed measures that could help non-locals buy land or land jobs in the Valley. Both the ruling National Conference and the opposition People’s Democratic Party (PDP) have accused the BJP of pushing policies that could alter the demographics of the Muslim-majority Valley.

Among the non-locals in the Valley is Mohammed Mia, a 38-year-old migrant from UP, who says he has been living “from hand to mouth”. “Many locals fear we would settle down here, now that there is no Article 370, but we just don’t make the kind of money that could make it possible,” says Mia. “The locals identify us from the Hindi we speak.” Back in the tenement, Muzamil says several migrants have learnt Kashmiri, but he finds the language “very difficult to pick up”.

According to Jammu-based political commentator Professor Hari Om, the “Dogri-speaking people who have suffered discrimination at the hands of the Kashmiri-speaking Muslim leadership” are demanding a separate state. “Jammu has been discriminated against, both politically and on the development front,” he says. “The chief ministers have always been Kashmiri Muslims, while Jammu has less seats in the legislative assembly even though its population would be found to be more if a census were conducted. There is a demand that the Dogra region, spread across 10 districts, including Rajouri, Poonch and Doda, should be carved out as a new state as the people have a distinct cultural identity, with an overwhelming majority speaking Dogri.”

Even as the demand for a separate state for Dogri-speaking people gains a foothold in the BJP-dominated Jammu region, leaders in the Union territory of Ladakh have sought a separate state for people speaking various Tibetic languages. Last month, the central government notified English, Hindi and Urdu, besides the local languages of Ladak—Bhoti and Purgi—as official languages. Ladakh MP Haji Haneefa Jan says the Centre was initially planning to include only Bhoti, but added Purgi, too, due to the demand of Kargil residents. “The cultures and languages of Ladakh are very diverse,” says the MP. “We are fighting to preserve its unique cultural and linguistic identity. This is why we demand statehood on the basis of language. Since Ladakh became a UT, it has been ruled by the bureaucrats.”

Meanwhile, following the row over the naib tehsildar recruitment, the BJP has pitched for the use of Hindi in official work as well as in academic examinations. “People cannot be discriminated against in recruitment for government jobs just because they don’t know a particular language,” says J&K BJP general secretary (organisation) Ashok Koul. “We have five official languages—Urdu, Kashmiri, Hindi, Dogri and English. We cannot tolerate policies that are discriminatory towards people who know other languages, while favouring those who know Urdu. We should not thrust one particular language on those who apply for government jobs. Anyone who knows Hindi or Dogri should be equally eligible for the posts. In fact, the authorities should take steps to promote Hindi.”

With post-370 Kashmir seeing signboards come up at several spots showing the distances of places in Hindi, too, besides Urdu and English, and with government websites displaying information in Hindi and Urdu also, not just in English, many local politicians have complained of a “cultural invasion”. “Use of Hindi in Kashmir is an attack on our culture, but the BJP won’t succeed in its designs,” says senior Congress leader G.N. Monga. National Conference spokesperson Imran Nabi Dar accuses the BJP of weaponising the language issue for vote-bank politics. “Urdu is not the language of Muslims alone,” he says. “Even in Jammu, people from other faiths read and write Urdu. The BJP has been trying to stoke communal fires by raising such issues.” PDP spokesperson Mohit Bhan agrees, saying the BJP’s opposition to the Urdu requirement for naib tehsildars is uncalled for. “Urdu is deeply rooted in India’s culture and serves as a bridge connecting people of all religions,” he says.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Ishfaq Naseem is senior special correspondent, 온라인 카지노 사이트. He is based in Srinagar.

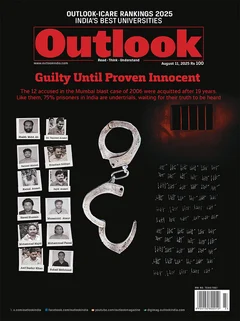

온라인 카지노 사이트 Magazine’s next issue, “Guilty Until Proven Innocent”, looks at the 19 years lost of those who were in jail and those who thought justice was served, until it wasn’t. This article appears as 'Divided They Speak' in the magazine