Imagine stepping into a dark cave, thinking you’ll be out in 15 minutes. But when you finally emerge from the cavern, 19 years have lapsed. And that overwhelming sense of suffocation that clings to you isn’t always visible to the outside world, unlike the streaks of greyed hair that mark the passage of time.

At the time, many questioned whether torturing suspects, even using electric shocks on their private parts, could ever be justified. But once someone is accused of killing 185 people, such doubts and concerns quickly fade. “But we were still in Arthur Road Jail,” says one of the men accused in the July 11, 2006 Mumbai train bombings, now known as 7/11. Somewhere along the way, the principle that a person is innocent until proven guilty was quietly forgotten.

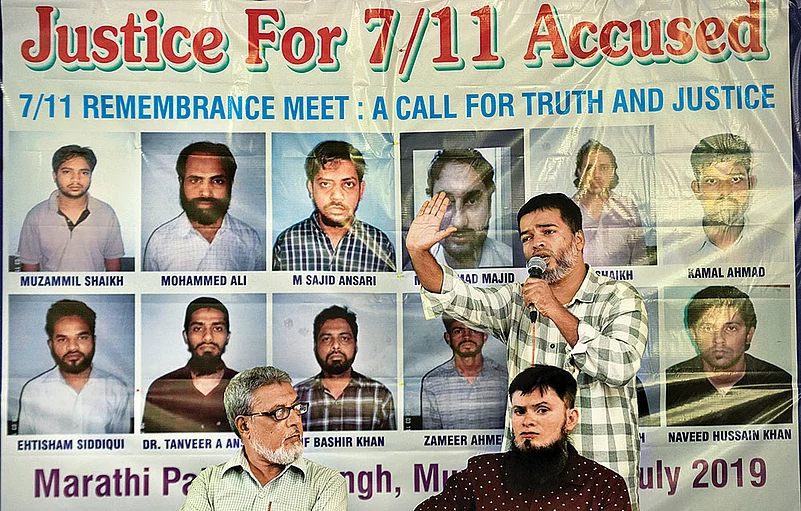

This is the story of those twelve men who were blamed for the deadly blasts, imprisoned, tortured and ultimately acquitted nearly two decades later.

Among them was Mohammed Sajid Margub Ansari (Sajid), listed as Accused No. 7. Sitting in his modest flat in Mira Road’s Naya Nagar, his breathing is uneven and his silent pauses are heavy. He had been released on a 40-day parole just before the Bombay High Court’s verdict that cleared the accused. It was as if the last 19 years swam before his eyes all at once. He held his daughter close, but it was the memory of prison and being behind cold metal bars, that still appeared to cling tighter. “When they first brought my child to see me, she cried. She didn’t recognise me,” he whispered.

His emotionally, mentally and physically draining 19-year ordeal began with what seemed like a routine police inquiry about the 2006 Mumbai train bombings. But for Sajid, it marked the start of a long, unforgiving chapter, shadowed by suspicion and social isolation. He had already been on the police radar. In the early 2000s, he was questioned for distributing pamphlets linked to the Students’ Islamic Movement of India (SIMI), an organisation banned in India after the 9/11 attacks in the United States. He had also been questioned after the 2003 Mumbai blasts. “Those (scars of) old enquiries never left me,” he says quietly. “They made me a suspect in the eyes of the system even when there was nothing to prove.”

Stigmatised by allegations and marked by his past, Sajid was forced to quit his job at a Nariman Point firm. The label of ‘suspect’ stuck to him like a second skin. He eventually found work at a small hardware and mobile repair shop in Mumbai’s Jogeshwari suburb, trying to solder his life piece-by-piece, just like he would fix broken mobile phones. Alongside he had opened up institute of the same.

July 11, 2006, began like any other day. Sajid had opened the shop with his employer Bilal and they were sorting through inventory. The city was bustling, Mumbai’s iconic ‘local’ trains were blitzing by and life moved at its usual frenetic Mumbai pace. Then came the sound. A loud blast. Tremors followed. “We heard a loud boom and felt the ground tremble beneath us,” he recalls, the memory still fresh. “There was construction happening nearby, so I assumed it was just something from the site.”

But it was no construction mishap. It was one of seven bomb blasts that tore through Mumbai’s suburban train network and the city’s psyche, killing 189 people and injuring over 800. The horror that unfolded sent shockwaves across the country and would soon shake Sajid’s life to its core. “In that moment, I had no idea those vibrations would shake the very foundation of my life,” he says.

Realising that the sound and tremor were not from the construction site, Bilal and Sajid ran towards the tracks and were among the first to help the victims. The two had no idea they were running into the eye of the storm. Sajid had goosebumps as he recounted the moment. Those memories still cling to him, even though he tries to outrun them.

Another accused in the serial blast case who was acquitted in July this year, Mohammed Majid Mohammed Shafi, was arrested in Kolkata. The charges against him? Arranging transportation for Pakistani nationals to Mumbai via the Bangladesh border and helping them return after the blasts. From within the grey walls of Arthur Road Jail, Majid would write letters to his wife back home. The anguish and resistance-laced import of Faiz Ahmed Faiz’s Saleebain Meray Dareeche Mein would echo through his words as he penned letter after letter to his wife from within the prison walls. Majid had been accused of helping perpetrators cross over from the Bangladesh border. “Maine unse baat karne ki koshish ki, magar…” (I tried talking to her, but), he wrote in one of his letters.

After the 2015 judgement, he could not write home anymore. He was found guilty. That verdict pierced more than just his fate. It devastated his wife too. A year or two later, her health deteriorated and both her kidneys failed. Strapped to dialysis paraphernalia, she would hold his letters close to her chest, hoping he would breathe free again. She passed away within three years, still waiting.

On September 11, 2015, a special Maharashtra Control of Organised Crime Act (MCOCA) court had convicted 12 of the 13 accused in the coordinated bombings that struck seven Western Railway suburban trains on July 11, 2006. The court found them guilty of conspiracy, murder and waging war against the nation, citing their alleged links to banned organisations like SIMI and Lashkar-e-Taiba.

Youngest And Strongest

Muzammil Ataur Rahman Shaikh was 22, the youngest of them all, when he was arrested. To this day, the stories of his time in different jails still send shivers down his spine. Months before the 7/11 blasts, Muzammil had joined Oracle Corporation in Bangalore as a software engineer. According to news reports, the Bangalore Police picked him up on July 13 that year but let him off, as he wasn’t in Mumbai on the day of the blasts. Soon after, the name of his brothers, Faisal and Rahil, came in the case, he was arrested again. Faisal still remains in jail for another case which was pushed against his name and Rahil was never caught.

But after 19 years, Muzammil walks out a free man only to find a house, not a home, awaiting him. During his time in jail, his parents passed away. While some of the other accused returned to families waiting for them, he was welcomed by empty walls. “I have become a burden on myself now,” he says. He wants to escape the noise and vanish into silence, but he cannot get rid himself of the thorn embedded permanently inside him.

In his house in the narrow lanes of Vikhroli, a Mumbai suburb, Wahid recalls the lives of his co-accused. One of them was Kamal Ansari, who had been accused of receiving arms training in Pakistan, ferrying Pakistani nationals across the Indo-Nepal border and helping plant explosives that later went off at Matunga station.

“He was the strongest amongst us,” Wahid says. Kamal’s mother adds, “Sometimes justice is delayed for so long that no one is left to see it.” Her son died in Nagpur Central Jail due to COVID-related complications in 2021. “They called me to see him and said his health had deteriorated.” She pauses. Her silence stretches as she visualises the small gap through which she identified her dead son kept in a prison room. “I was only able to see his back. He was already dead.”

From within the grey walls of Arthur Road Jail, Majid would write letters to his wife. The resistance-laced import of Faiz Ahmed Faiz’s Saleebain Meray Dareeche Mein would echo through his words.

Recalling Kamal, Sajid alleges that the medical treatment given to him during the pandemic was inadequate. “The jail did not treat him well. If there was better treatment, he would have been breathing with us,” Sajid says.

The issue of poor conditions at Mumbai’s Arthur Road Jail, where all the accused were kept until the 2015 judgement, had been raised repeatedly with the superintendent and in court. Sajid, speaking with frequent pauses, describes how five of them were made to share a small cell. “Two batches (involving) people arrested in the 7/11 and Malegaon blast cases were merged. We were kept in rooms where three small holes near the grey cement ceiling gave us a little ventilation, light and hope. The mat we had to sleep on was so thin it would soak through with our sweat. The rooms were very hot and it was only in the middle of winter nights that we felt a little cold,” Sajid recalls.

Describing the torture and violence they endured, Sajid takes small gulps and says he wouldn’t wish it even upon his enemies. One incident that both Muzammil and Shaikh Mohammed Ali Alam Shaikh remember clearly is when they were given electric shocks to their private parts.

Shaikh Mohammed was accused of providing his house in Govandi for making bombs. Now sitting with his two sons, he casually twists his elbow, which cracks softly. “Do you hear that sound? There is a ligament issue that makes the noise. Currently, I am undergoing treatment and taking medication for this,” he says.

These tales of violence, which left scars both visible and hidden, brought nothing close to justice… or closure. A complaint was filed in court in 2023, Sajid says, but before the court could act, the superintendent from that period raised a “false alarm”—a term in jail for a warning of impending inmate violence. “They tortured us to the extent that we urinated blood,” says Sajid.

Despite the brevity of the moments, the accused never seem to forget the short time they had with their families when in incarceration. These few minutes, in which conversations meant for years were crammed in, gave both sides a fleeting sense of relief. But the time spent behind crumbling bars, with their own horror stories etched into the walls, changed the kind of husbands, fathers and sons they became.

Sajid still cannot come to terms with not being there for his daughter the way a father should have been. The absence feels like a gorge. His mother passed away while he was still in jail, and though he was allowed to visit, it was under heavy police watch. “I visited my mother when she was in the ICU. My brother whispered in her ears, Ammi, Sajid aaya hai (Mother, Sajid is here). I had only ten minutes and had to leave. When she opened her eyes for the last time, she asked, ‘Where is Sajid?’ And I was just not there.” In 2006, the police escort charge was Rs 5,000 to Rs 6,000. Today it has increased to Rs 2-5 lakh. The police escort fee varies depending on the nature of the charges against the inmate. It is determined by the severity of the crime and the salaries of the guards assigned to accompany the prisoner.

Wahid remembers how Majid once cried through the whole night. His daughter had told him during a visit, “Abbu, if I hug you and pretend to be asleep, will they let me stay ten minutes longer?”

“There are thousands of guilty, accused men in jail,” says Sajid, “but then there’s another category: terrorists. Everyone thrashes you like an insect. And their anger is justified, if they’re sure that we are the culprits.” He kept repeating, “If not?”

He was among those encouraged by Shahid Azmi, a human rights lawyer, to study and make use of their time in jail. Azmi himself had been falsely arrested at 15 in connection with the 1992 Bombay blasts and went on to become a ‘masiha’ (messiah) for many caught in terror cases. He, along with Ehtesham Qutubuddin Siddiqui, another accused, completed law studies while in jail. Ehtesham spent nine years as an undertrial and took several educational courses through IGNOU, including an MA in English and a master’s degree in management studies. He eventually published his book Horror Saga in 2024, where he writes, “Because this was a setting/Hence, forget about telling anybody/What happened in custody.” The juxtaposition is poetic: beautifully painful.

Justice Undelivered

Nineteen years may have passed since that terrifying evening in July 2006, but for Muzzammil, Shaikh Mohammed and Sajid, time hasn’t eased the ache. Their memories are not just personal; they are shared. They echo through the city’s train compartments, lingering in the silence between stations. Amid the grief, they are still searching for answers and justice from the government, the police and the judiciary. “What happened to us should not happen to anybody. We spent our lives in jail, thinking justice is a step away. But now it is the responsibility of the authorities involved to deliver justice,” Muzzammil says, a spark in his eyes.

For Sajid Qureshi, now in his early forties, spending time with his children has become his anchor. “You can either let pain harden you, or let love soften you,” he reflects. “My wife, she never stopped believing in me. My kids don’t know everything, but they know enough to understand that life is fragile.”

All the men share a sentiment that is hard to miss. They do not want to be defined by tragedy or suspicion, but by resilience and compassion. Their voices carry more than stories of loss. They carry the quiet weight of hope. Hope for truth. Hope for justice. And, above all, hope for healing.

As Mumbai rushes forward with its unrelenting speed, these men, once caught in the blast’s aftermath, now seek slower, more meaningful moments. “Our families taught us how to live again,” Sajid says.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Pritha Vashishth is 온라인 카지노 사이트’s Mumbai-based correspondent

Jinit Parmar is a senior correspondent, 온라인 카지노 사이트. he is based in Mumbai

온라인 카지노 사이트 Magazine’s next issue, “Guilty Until Proven Innocent”, looks at the 19 years lost of those who were in jail and those who thought justice was served, until it wasn’t. This article appears as