This article is part of a three-part series breaking down the technical and thematic aspects of the Netflix series 'Adolescence". Read Apeksha Priyadarshani's "A Technical Masterpiece Exploring Teenage Misogyny" and Tatsam Mukherjee's "The Nightmare That is School"

In Netflix's 'Adolescence', when DIs Bascombe and Frank reach Jamie’s school to conduct enquiries and interrogate his classmates, a terrifying, bigger picture emerges. How does the vicious online world drive the moods and whims of teens? This sequence chillingly establishes that Jamie isn’t some anomaly or has horribly strayed; his school has scores of his likeness. His actions are emblematic of an entire ecosystem where his crime is the ultimate station of a set norm. Most of the students are all perfectly capable of tipping over the edge, Jamie just happened to take the plunge. Frank memorably describes the regular smell of a school: “sweat, vomit and masturbation”. There’s screaming, rowdiness, bullies ganging up everywhere. A banner hanging outside the school reads: “Stop knife violence.”

With raging hormones and nerves that fly through the roof, the students’ volatility, their constant readiness to rear knives and pull aim make for one of the series’ most suffocating sections. To engage with them is to tread eggshells. The other constant is the phone that’s in everyone’s hands.

Online scrutiny compounds the social image teens have to keep up. Their envy, insecurity, perceptions of their bodies and equations with others get riled up when refracted through the prism of virtual projection. Students are perched on the very precipice; a small trigger can make them erupt into violent, cussing confrontations. Jade, the slain girl’s best friend, has a difficult situation at home, an uneasy relationship with her mother. The minute she suspects someone of the murder, she attacks him in the open, spurred by anger for having her only safe, happy space ripped away.

In the single, unbroken take, the camera dashes through classrooms, down stairwells and hallways, leaping into the courtyard—an uninterrupted chain-link of windows into an environment dripping with casual violence. Teachers scramble to bring order. Power, instead, remains with the students themselves, who mock, laugh at and patronise the teachers, unconcerned with consequence.

We witness the generational gap reveal itself, teachers and parents terribly unequipped to understand how teens see and interact with the world. Their opinions are entirely shaped by online communities, a world alien to the guardians. One of the educators says she’s heard of Andrew Tate being mentioned by students, but she knows nothing more. Most of the students keep themselves guarded or try to dodge the authorities’ questions.

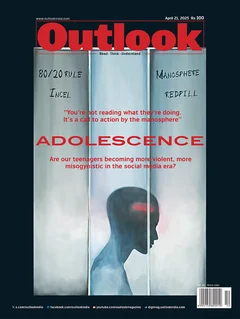

The DIs end up running into half-baked conclusions. It takes Bascombe’s son Adam, a student at the same school, to clear the air and put things in perspective. He tells his father how embarrassing it was to watch him fumble before his classmates. He gives him a rundown on emojis the girls use on Instagram, referring to the manosphere of incels. There’s the 80:20 number governing the female-male attraction game. Only a marginal percentage of men get noticed, Adam confides in his clueless father. It’s a theory pushed by Tate, the manosphere supremo.

Katie thought Jamie was an incel and publicly called him out, leading to the latter’s revenge. Bascombe takes some time to process this. How can mere emojis shove someone into murder?

There’s a veil between the father and son. Adam himself is bullied at school, which Bascombe observes in a class he staggers in, yet baulks discussing it openly. How much can Adam share with his father?

All it takes, Frank remarks, is just one person—be it a teacher or parent—to assure the kids they’re alright. It takes no special intuition to guess her school memories aren’t particularly pleasant either. She wants to get the job quickly done and head out.

UK has just decided to show Adolescence in secondary schools to flag awareness into online perils. But how far can this step take the conversation forward without being backed by proper policies? It’d be nothing but occasional lip-service tailored to the season’s sensation. All stakeholders need to partake in the conversation with urgency, rigour and empathy.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Debanjan Dhar is a film fest-junkie & is fascinated by South Asian independent cinema

This article is part of 온라인 카지노 사이트’s April 21, 2025 issue 'Adolescence' which looks at the forces shaping teenage boys today—online misogyny, incel forums, bullying, and the chaos of the manosphere. It appeared in print as 'The Nightmare That Is School'.