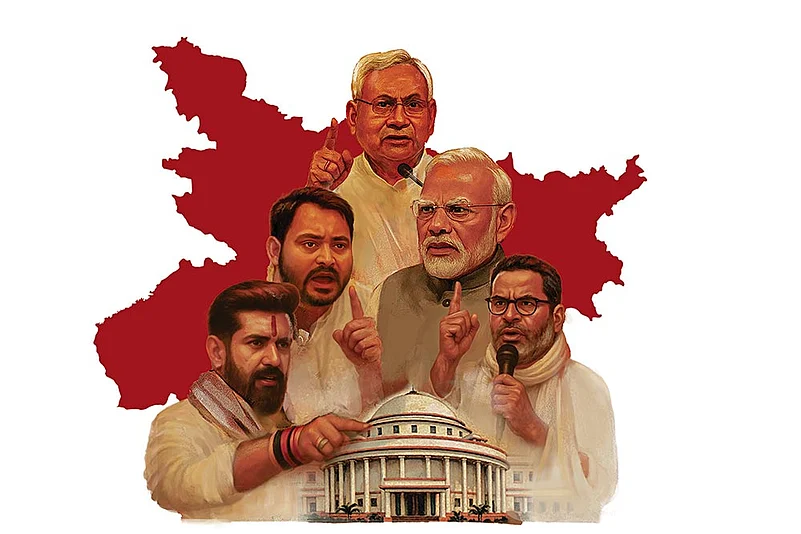

As Bihar heads into the 2025 assembly elections, it finds itself at a historic inflection point. This may well be the final electoral face-off between the two stalwarts who have defined the state’s politics for more than three decades: Nitish Kumar and Lalu Prasad Yadav. While Nitish remains the chief ministerial face of the National Democratic Alliance (NDA), Lalu, though not on the ballot, still looms large as the guiding light of the Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD)-led INDIA group.

What began in the 1970s as student activism during Jayaprakash Narayan’s (JP) ‘Total Revolution’ has now come full circle. The very leaders, who once marched side by side during protests, are today overseeing the transition to a new generation of post-Mandal politicians. As Bihar stands on the cusp of this generational shift, the real question is: what kind of politics will shape the state’s next chapter?

Bihar has long been a crucible of political change in India. From being among the first states to abolish the zamindari system after Independence to birthing the socialist wave that challenged the Congress’ hegemony, the state’s political history is deeply intertwined with the country’s democratic evolution. Bihar was among the first states where the Congress lost power in 1967, and it was here that the JP movement, the most significant post-Independence people’s movement, took shape in the mid-1970s. That movement seeded an entire generation of leaders like Lalu, Nitish, Ram Vilas Paswan, and Sushil Modi.

After a decade of instability and musical chairs in the 1980s, driven as much by the whims of Indira and Rajiv Gandhi as by grassroot unrest, Bihar’s political landscape changed decisively in 1990. The Janata Dal came to power in a politically fragmented era. The Congress, which was already tarnished by the Bhagalpur riots of 1989 and afflicted by a growing perception of upper-caste bias—especially with all five Congress chief ministers in the 1980s coming from upper castes—lost the trust of its most loyal vote bank: the Muslims.

“The defeat of the Congress in 1990 marked the end of an era in Bihar’s politics, which can be best described as ‘feudal democracy’… The Congress had failed to deliver on the promises of poverty alleviation, land reforms, ending discrimination and providing dignity for Dalits and the Other Backward Classes (OBCs). Moreover, the Bhagalpur riots made it lose its ever-loyal Muslim vote bank too.” (An excerpt from Broken Promises: Caste, Crime and Politics in Bihar).

Lalu’s early years were marked by an assertive empowerment of backward classes, but over time, his regime became synonymous with grave misgovernance, flourishing crime syndicates, caste wars, economic stagnation, and the virtual Balkanisation of Bihar under ruling Bahubalis (mafia dons/criminal politicians). While a formidable combination of Yadavs and Muslims kept Lalu in power till 2005, that year also marked the peak of public frustration with the state’s collapse.

Enter Nitish. Riding a wave of hope and backed by the NDA, he turned the narrative around. His first term (2005-2010) saw a remarkable transformation—roads were built, crime rates fell, villages were electrified for the first time since independence and there was a marked change even in other areas such as government schools and health centres. For a while, it seemed Bihar had finally found its architect of modernity. Some of his socialist policies, such as the sub-categorisation of OBCs into OBCs and Economically Backward Classes (EBCs), and reservation for women in panchayats, won accolades across the country.

“When Nitish Kumar became Bihar’s new chief minister, his role was far from enviable. Nitish’s style and approach was diametrically opposite to that of Lalu’s... While Nitish was credited with a lot of good work as cabinet minister in the NDA government between 1998 and 2004, fame and recognition would elude him until now. Many insiders from the railway ministry often credit Nitish’s initiatives for the railways’ turnaround, which Lalu later executed during the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) regime.... Nitish realised during these ministerial stints that development could be good politics. Also, Bihar being at the bottom of all development parameters, he would garner both recognition and votes if even the basics were done right. However, Nitish had not just inherited a state with the worst economic and human development parameters, but also a state apparatus with a corrupt and resigned bureaucracy.” (An excerpt from Broken Promises: Caste, Crime and Politics in Bihar).

But Nitish’s journey hasn’t been linear. His frequent realignments with the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), then the RJD, and back again, have eroded the moral clarity that once distinguished him. The flip-flops have been seen by many as political opportunism. Yet, despite the ideological zigzags, he has remained central to Bihar’s power structure.

Nitish’s journey hasn’t been linear. His frequent realignments with the BJP, then the RJD, and back again, have eroded the moral clarity that once distinguished him.

Elections in Bihar have never lacked drama, but 2025 feels different. Not just because it may mark the end of the Nitish-Lalu era, but because it could signal the beginning of a new political discourse altogether. Bihar today is younger, more aspirational, and far less patient with politics rooted solely in identity. The erstwhile issues of roads, electricity, and water have now evolved to migration, unemployment, and economic distress. The rising number of first-time voters is reshaping expectations. They are less interested in slogans of social justice and more focused on jobs, education, and dignity.

In that sense, Bihar may be experiencing what Uttar Pradesh did in 2017: a shift from caste arithmetic to governance-centric politics. Whether this shift is deep enough to change electoral outcomes remains to be seen.

Despite rising aspirations, caste still plays a defining role in Bihar’s elections. The NDA, led by the BJP and the Janata Dal–United (JD(U)), enters 2025 with a stronger coalition than in 2020. The return of Chirag Paswan’s Lok Janshakti Party Ram Vilas (LJP (RV)), Upendra Kushwaha’s Rashtriya Lok Samata Party (RLSP), and Jitan Ram Manjhi’s Hindustani Awam Morcha (HAM) has bolstered the alliance. In 2020, the JD(U) suffered heavy losses, partly due to Chirag’s rebel candidates. An internal analysis suggests that the NDA could have won at least 35 more seats had the LJP (RV) stayed within the fold.

On the other side, the INDIA group is anchored by the RJD, with the Congress, the Left, and Mukesh Sahani’s Vikassheel Insaan Party (VIP). The core M-Y (Muslim-Yadav) vote remains its strongest asset, but it will also try to attract segments of EBC and Dalit votes. The RJD’s recent appointment of Mangani Lal Mandal, from the EBC community, as state president is a step in that direction. The EBCs—which comprise 112 castes and constitute over 36 per cent of the population—are the largest voting bloc and have historically aligned with Nitish. The Congress is also expected to bring in some upper caste votes.

For now, the NDA appears more formidable. Anyway, as seen over the last two decades, whichever side combines two of the three major players—the BJP, the JD(U), and the RJD, tends to win. That makes Lalu’s repeated public signals of openness to realigning with the JD(U) all the more noteworthy. Nitish, however, has insisted since the 2024 Lok Sabha elections that he’s staying with the NDA “come what may”. Many remain sceptical, given his past, but it does appear he wants to be remembered for Bihar’s turnaround, not just for political manoeuvring.

If the 1990s was the decade of political upheaval, the 2020s could well be the decade of succession. Tejashwi Yadav, Lalu’s son, has already taken charge of the RJD. Chirag is positioning himself as a modern, pan-Bihar leader—signalling this shift by announcing his decision to contest the upcoming 2025 election and that too from a general seat. This is a clear attempt to expand his party beyond the traditional Paswan vote base. In doing so, he also appears to be moving away from his father’s politics, which was often more Delhi-centric. Within the JD(U), senior leaders are lobbying to bring Nishant Kumar, Nitish’s only son, into the political fold. Given that most regional parties in India struggle to survive without a clear dynastic successor, this push is seen as a last-ditch effort to preserve the party’s future in the post-Nitish era. Nishant, however, has so far kept a studied distance and avoided a clear answer.

This generational shift raises a fundamental question: are these young leaders merely inheriting power, or are they capable of offering a new vision rooted in Bihar’s present day realities? Questions around the educational qualifications of the RJD’s heir, Tejashwi Yadav, have often surfaced, and not without reason. The recent controversies surrounding his brother, Tej Pratap Yadav, particularly those stemming from personal and family disputes, have further fuelled concerns about the family’s next generation’s political maturity and public conduct.

Adding complexity to this transition is the emergence of first-generation political actors like Prashant Kishor, founder of the Jan Suraaj Party. Having undertaken an extensive padyatra across Bihar, Kishor has consistently raised pressing issues—governance, education and employment—with technocratic clarity. Yet, in a state where electoral choices are often shaped more by caste loyalties than issue-based politics, the critical question remains: can idealism translate into electoral strength?

Bihar’s past has often overshadowed its potential. Its intellectual and cultural contributions to India are immense, yet its contemporary image is shaped by poverty, migration, and underdevelopment. That dissonance is now fuelling a silent churn.

The 2025 elections may not just determine who governs Bihar, but it may also define how Bihar is governed. Will caste remain the dominant currency, or will governance, infrastructure, education, and employment take centre stage? More importantly, will Bihar’s political class finally move from slogans to solutions?

Whatever the outcome, one thing is certain: 2025 will not just be a battle of alliances. It will be a referendum on legacy, leadership, and Bihar’s hunger for change.

(Views expressed are personal)

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Mrityunjay Sharma is the author of Broken Promises: Caste, Crime And Politics In Bihar.

In Jungle Raj, 온라인 카지노 사이트’s August 1 issue, we explored why the Bihar elections matter so much. Our reporters delved into the state’s caste equations, governance records, electoral controversies and national ambitions, along with taking a hard look at the law and order situation— all of which make the 2025 Bihar Assembly elections one of the most consequential state polls of this electoral cycle. The article appeared as 'What’s The Bihar Model?'