It’s a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma—why is India’s total fertility rate, or the children born per woman over a lifetime, not lowering uniformly across the country? Indeed, the North-South divide recently spilled over into the political space over this issue, when the delimitation of electoral constituencies hit headlines.

To explain, let us begin with a story from the North, of three women in Bihar, where the fertility rate is 3.0, the highest in India in 2021, according to the National Family Health Survey.

Each of these women belongs to a new generation, and each exemplifies the great strides India has taken in the decades since Independence when it comes to population control.

The first women, Saraswati Devi, had five children—all sons—by the time she turned 30 in 1976.

Then came her daughter-in-law, Anita Devi, who had six children in the 1990s. “I felt exhausted,” she says, “but I had little say in the matter.”

And finally we have Anita’s daughter, Pooja Kumari, who had her first child at 23, in the 2020s. A government healthcare worker she met gave her birth control advice, as a result of which, she hadn’t had a second child, one she’d been planning for.

These women of a family feature in the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA)’s 2025 edition of the “State of World Population Report”, titled “The Real Fertility Crisis”. The story of these women of a family throws some light on the positive changes in one of India’s least developed states.

However, on 15 November 2022, the global population hit , and soon after, in April 2023, India became the world’s most populous nation, overtaking China. India’s population is expected to reach 1.7 billion by the 2060s, before a real deceleration in fertility starts showing results.

Consider the global perspective: The world took twelve years to go from seven to eight billion people. It will take another fifteen to swell to nine billion. That’s how slow the impact of fertility declines is.

India’s case is unique because despite having made progress, it still has pockets of high total fertility rates.

“India has made significant progress in lowering fertility rates—from nearly five children per woman in 1970 to about two today—thanks to improved education and access to reproductive healthcare,” said Andrea M Wojnar, UNFPA India Representative in the same report.

According to the UNFPA, India has a dual crisis: The issue here isn’t too many or too few children, but the inability to achieve the number of desired children.

At least one in three adult 온라인카지노s fall unintentionally pregnant, while 30 per cent have an unfulfilled desire for fewer children.

Over the years, 온라인카지노 women have acquired greater control over how many children they have, but that progress has been much slower in, for example, Bihar, Jharkhand, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh. By contrast, southern states, especially Kerala and Tamil Nadu, have sustained below-replacement fertility rates—2.1 and below.

This is a clear reflection of disparities in economic opportunities, healthcare access, educational attainments, and the influence of prevailing gender and social norms.

Besides, deep inequalities persist across states, castes and income groups even within regions that have demonstrated striking success in reducing fertility rates.

The next population census, beginning on March 1, 2027 is now expected to drive significant policy changes, including on the caste/equity front, as an enumeration of castes is to be included in the overall data-collection.

Therein lies the rub: The states that have curbed fertility rates—mainly in the south—fear they will be disadvantaged after the next census. This is because it could precede the restructuring of parliamentary constituencies based on the new numbers.

As a result, a new argument is circulating in the 온라인카지노 political space—that a vote should not just be counted as a number but measured in terms of its value. When populations across regions are not uniform, then constituencies adhering to these divergences can get greater value.

Here’s why: Currently, the southern states have a 24 per cent share of Lok Sabha seats. Once boundaries of Lok Sabha and State Assembly constituencies are redrawn, based on the new population figures, these states—along with smaller northern states such as Punjab, Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand, and the northeastern states—will be at a disadvantage compared to the larger (more populous) northern states.

In other words, it will still be one person one vote—but with more persons in some region, their representation will rise disproportionately. The southern states view this as a penalty for having fought hard to reduce their population growth rates.

Based on the 1971 census, the number of seats in Lok Sabha was fixed at 543. At the time, India’s population was only 54.8 crore.

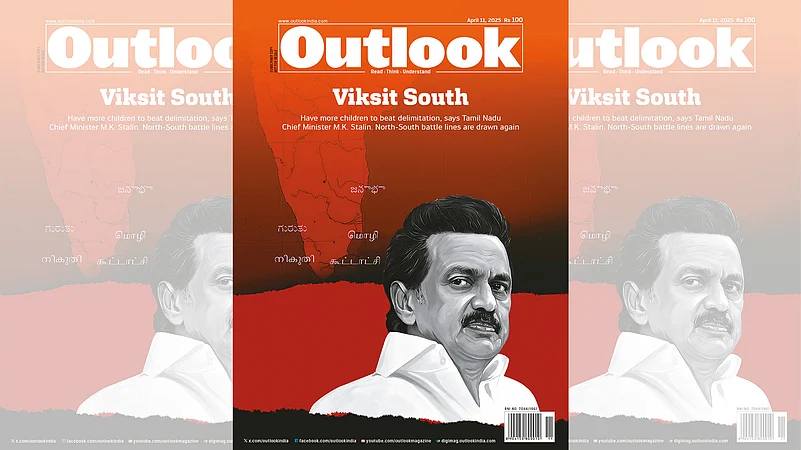

Under this scenario, their share is projected to decline by 5%, and by extension their political influence. The issue was dealt with in 온라인 카지노 사이트 Magazine’s April 11, 2025 issue, ‘Viksit South’.

Palanivel Thiaga Rajan, the well-known Minister for Information Technology and Digital Services of Tamil Nadu writes in ‘The South’s Concerns About Delimitation Are Well-Founded’:

: “…in India, the states (largely in the South) which disproportionately drive the national Gross Domestic Product have much smaller populations and lower fertility rates. Conversely, the large northern 온라인카지노 states, which contain the nation’s largest populations (and have the highest fertility rates), suffer from the greatest rates of poverty, and significantly lag the national average on most development and economic indices.”

Supreme Court senior advocate Sanjay Hegde in ‘We Need A New Delimitation Formula’, explains the fears of southern states and why they are valid. Due to these fears “several wise governments” decided to kick the delimitation can further down the road, he writes. “The 1976 delimitation freeze was extended repeatedly. The 2001 amendment pushed any change to 2026.”

Hegde writes that lifting the freeze on delimitation will shift India’s political map dramatically: “The North will gain seats. The South will lose influence. Is this fair? Hardly. Representation is not just about numbers. It is about governance. It is about acknowledging effort and progress.”

(Why should not this be done again is the unspoken question here.)

Kavitha Muralidharan writes on Tamil Nadu having to push back against “Delhi’s heavy-handed centralism”, reminding readers of the anti-Hindi agitations of the 1930s and 1960s, the battle against the National Eligibility Cum Entrance Test (NEET) and the National Education Policy (NEP). “…Tamil Nadu has repeatedly found itself confronting a Union government that mistakes cultural diversity for defiance. The tyranny of numbers is often invoked to justify the next delimitation exercise”, she writes in ‘Delimitation: Will South Pay the Price for Delhi’s Negligence?’

A swelling population fuels and elevates the push and pull between dominant and non-numerically dominant groups. It makes the future course of a nation appear inevitable, even natural, when it isn’t either. But it also ignites urgent conversations about women, whose agency and reproductive freedom are still contested battlegrounds; about language, which sculpts the very architecture of thought and forges the shared lore of a people; about how entire populations can be turned into weapons against each other with chilling ease.

Yet, look at what we have achieved together—monuments that defy the centuries, machines that slip the bonds of Earth to explore the stars. Even now, as you read these words, humans orbit above us in the International Space Station, a testament to our boundless ambition.

Eight billion people on one fragile planet with an expiration date. Perhaps, World Population Day is the moment to stop and ask ourselves: What if we could strip away the borders, the politics, the hierarchies—and see ourselves as a single species, devoid of all the other lines we have drawn between ourselves?

Or at the very least, try—if only for as long as we can.