Vikramaditya Motwane’s Udaan (2010) slipped into theatres fifteen years ago with the hush of a secret too painful to shout. For many of us who watched it, Udaan detonated like a quiet bomb—disrupting and digging up memories we’d buried, and naming wounds we had never dared describe.

Udaan articulated what so many 온라인카지노s still carry but cannot say: sometimes, for many of us, the first prison is home. It gave realisation to the idea with devastating clarity that the house is not always a haven. It is the cage we’re told we’re lucky to have.

I remember watching it and immediately wanting to write about it. Eventually, I did. I wrote a piece on parental abuse, with Udaan as its anchor. I poured into it everything I’d felt growing up—the way our culture sanctifies violence in the home, how it dresses up bruises as discipline, and calls fear by other names: love, tradition, respect. All this, only to be told by the editor to soften the sentiment because we wouldn’t want to “offend” the parents, who “have a right” to choose how they raise their kids.

In 온라인카지노 culture, an occasional slap, the sporadic hair grabs, and other forms of physical violence are often rationalised. Alarmingly enough, it is seen as either tradition, affection, or necessary toughening-up. But what Udaan did was strip all that cultural justification down to its bruised bone.

As someone who grew up in a violent home, Udaan was a hard watch. The belt. The silences. The stares. The smell of alcohol—palpable through the screen—made my skin crawl. Ronit Roy’s performance was exceptional. It was pitch perfect and a little too unnerving for my comfort. It felt like holding a piece of agonising memory I did not want to carry with me anymore—which is also perhaps why I have not been able to revisit this film. As is the case with so many good films, once is enough to leave a permanent mark.

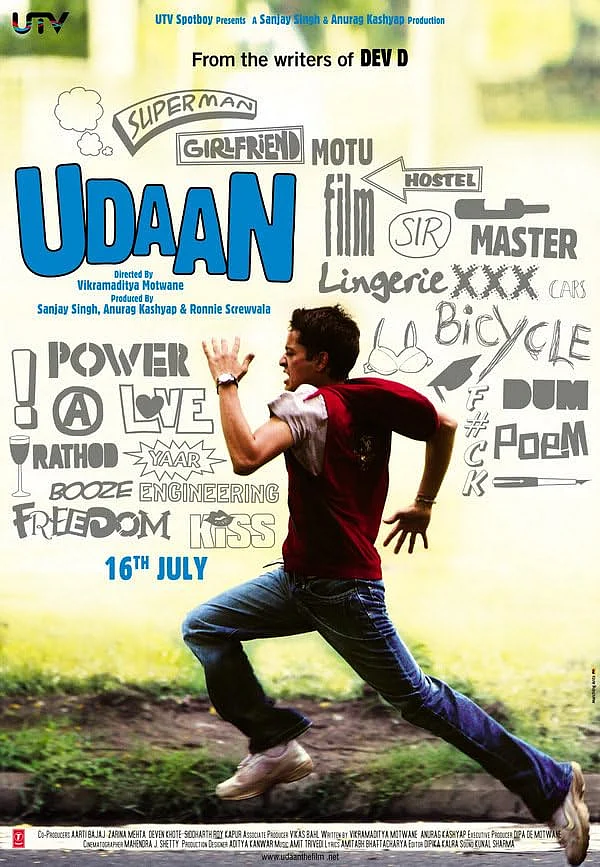

Udaan made it to the ‘Un Certain Regard’ competition at the 2010 Cannes Film Festival, received its critical laurels, but only gained traction through the sinewy routes of torrents and streaming platforms. The film, co-written by Motwane and Anurag Kashyap, sparked a small but significant wave of coming-of-age and intimate personal storytelling in Hindi cinema. Especially in the independent space, it brought in its wake brilliance like Stanley Ka Dabba (2011), Titli (2014) and Masaan (2015) among others.

Around this time, there was a resurgence of a genre that can be best described as “indie-mainstream”, or Parallel Hindi Cinema 2.0, as some called it—it was the mood of the season and film lovers everywhere in India were loving every bit of it.

Udaan told the story of Rohan, a 17-year-old boy expelled from boarding school, forced to return to his small-town home in Jamshedpur and live with a cold, authoritarian father he barely remembered as a young adult. The film captured the suffocating atmosphere of patriarchal households, where discipline becomes abuse, and obedience is demanded in lieu of affection. It held up a mirror to the type of masculinity that fathers pass down like a family heirloom—silent and so terribly angry.

Rajat Barmecha, as Rohan, delivered a performance full of so much ache. It is a shame the industry could not give him a bigger platform. Barmecha’s Rohan wasn’t a Bollywood rebel. His pain was internal and his defiance—as he chinned up to break the chains—was quieter. When he wrote poetry in secret or snuck out to smoke with friends, it was less like teenage angst and more like small acts of survival. There was a maturity in Barmecha’s performance that made you believe every unshed tear and held-back scream.

The cinematography by Mahendra Shetty turned Jamshedpur’s factories, railway tracks, and crumbling homes into symbols of entrapment as well. Amit Trivedi’s music added a layer of hope and momentum. Tracks like “Azaadiyaan” and “Kahaani (Aankhon Ke Pardon Pe)” as well as the score were woven with pain, but also with the electric possibility of escape.

There’s a moment near the end, when Rohan finally confronts his father and walks away from home, from inherited violence, from silence, from a life of being stifled. It’s not a grand, heroic act. But in that quiet rupture lay the full weight of what Udaan wanted to say. Running away is sometimes the only option that does not scar further.

For many of us who grew up navigating violent homes, Udaan also leaned into the familiar fantasy of an elder sibling who would one day come to save the day. The film gave that unspoken hope a face.

In the years since, Motwane has expanded his range, but not lost his vision. With Lootera (2013), he proved he could do sweeping romance with lyrical grace. Bhavesh Joshi Superhero (2018) was ambitious, flawed, but refreshingly political. It was a vigilante film driven by disillusionment, not fantasies of power. AK vs AK (2020) was subversive and self-aware. Across these films, you can trace Motwane’s constant: his love for broken men trying to stitch themselves back together by defying the moulds the world tried to put them in. His refusal to give in to easy closure and his ability to make the personal feel universal has been a boon to cinema, to Bollywood.

Fifteen years later, Udaan remains one of 온라인카지노 cinema’s landmark films. It wasn’t the first to talk about abuse or rebellion, but it did so without artifice. It didn’t offer blood and vengeance, but the sweet relief of escape earned through sweat and tears.

Debiparna Chakraborty is a film, TV, and culture critic dissecting media at the intersection of gender, politics, and power