Bracing candor saturates this intense character study of an obstetrician in Georgia

It's a masterly study of the forbidden

The director fuses the hyper-real and surreal to startling effect

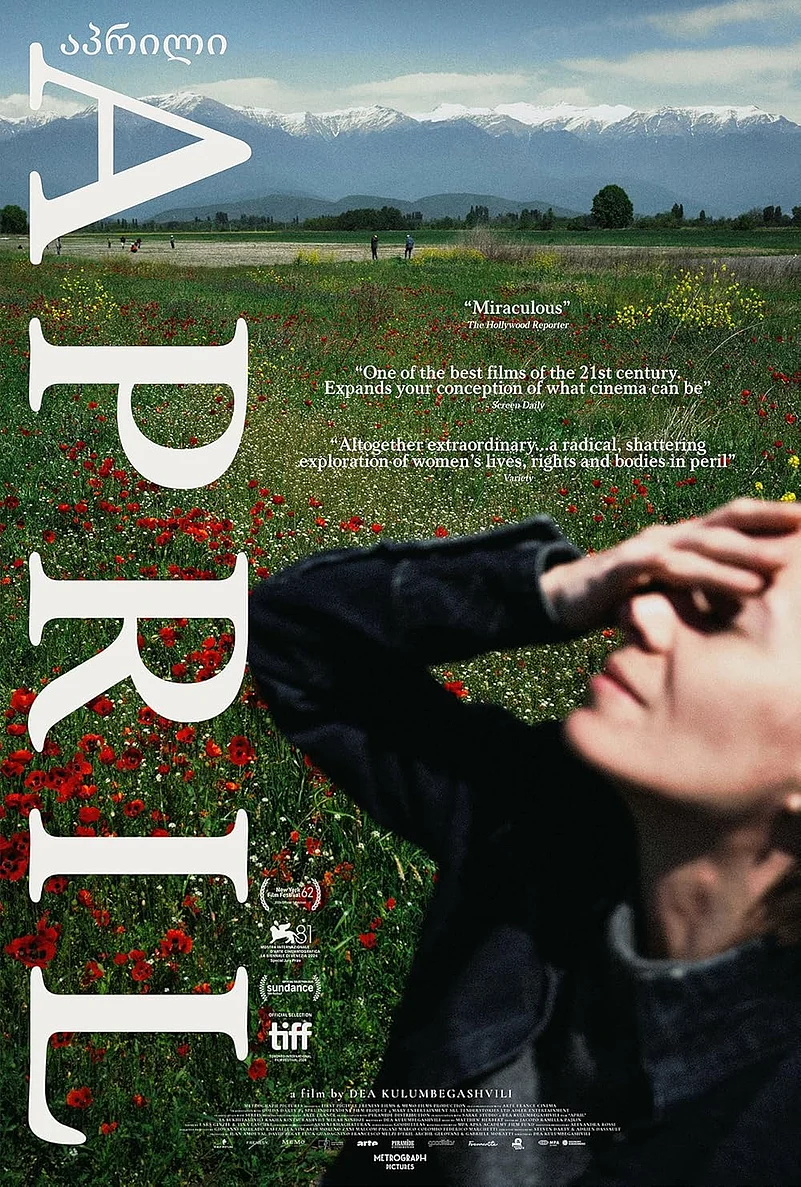

With just two features, Beginning (2020) and April, Dea Kulumbegashvili has mastered the art of long takes. In her hands, they are penetrating tools, splicing through the viewer’s discomfort and exposing the repressed. An OB-GYN, Nina (Ia Sukhitashvili) is cool-headed and confident at her job. She might have gone much farther if she didn’t also conduct abortions in clandestine. In Georgia, abortions are just narrowly legal, but society hasn’t caught up yet. Catholicism, followed to the letter across the country, compounds the matter. Thus, Nina’s secret acts are laced with peril. But Kulumbegashvili isn’t a filmmaker prone to predictable rhythms or staid narrative patterns. Amidst April’s unrelenting passages, there are strange figures and sensations suddenly thrusting forth. Surreal intrusions push an otherwise forbiddingly solemn trajectory off-centre. A literal spectre of Nina’s guilt and buried emotions flicks through spaces—both at her place, watching her at a distance, and from outer expanses. It takes the shape of an amorphous creature, a humanoid stalking the edges of the film. A startling appearance throughout the film, its skin sags and it wants to say something but cannot. At other times, fields filled with bright red poppy flowers puncture a linear vision with handheld energy.

Early in the film, Kulumbegashvili jolts us with bracing frankness. We’re planted in the middle of a live childbirth. Initially, it seems to have gone well, until a long shot of Nina alone in the hospital corridors suggests it didn’t. Kulumbegashvili assembles dread and blanching unease that stretches into every fibre of one’s being. She lets it accumulate so strongly that it hangs to each scene like an abiding truth. For women, fear is a constant reality that doesn’t magically dissolve by gaining a solid job, or an apparently powerful position. Agency is always precarious—at a risk of being taken away on whims and cruelties of men just because they can. Patriarchy and religious conservatism twin as double threat, trespassing and forcing themselves on women. Choice is unheard of. Immediately, Nina is accused of deliberately mangling the delivery. The aggrieved husband spits at her, adding that he is aware of her doing abortions in villages.

To share Nina’s subjectivity is to be unerring witness to her tight-coiled existence. One could argue, however, that April isn’t really extending or emphasising an absolute know-it-all, transparent subjectivity for Nina. There’s a certain degree of reserve, a coldness and inherent mystery in Sukhitashvili’s formidable performance. Her breathing forms an integral part of April’s sonic underbelly. It’s fascinating to watch an actress refuse to feed easy cues. Her face often toughens into something impermeable, impassive. She repels one’s efforts of establishing familiarity. There’s something resolutely dignified about her, while also guarding uncomfortable, dark secrets. Nina’s demeanor shifts into inscrutability, a glacially unsympathetic pose, when surrounded by male colleagues/superiors. They project an attitude of interrogation, reminding her of boundaries she cannot cross. Neither does she let slip what’s on her mind. There are long stretches, especially those dovetailing Nina’s stance on intimacy and sexual encounters, where the actress retains a jagged ferocity and drifting detachment in the same breath.

Sukhitashvili implies a firm conscience, which makes it almost impossible for Nina to kowtow to social norms. Nina can’t stomach pushing women into a hellhole when she does have some means to prevent it. But her reach is only limited. She treads cautiously, holding her breath while straddling the line between her humane impulses and dangerous mores. She knows she has everything to lose if her enabling abortions leaks into the open. But are her interventions wholly led by compassion alone? The performance hints at something Nina has long stifled—trauma just below the bone. When an ex pokes her about her current love life and having kids, she brushes him off. We follow Nina through late-night drives, visits to villages, quietly pounding with immense risk. These grow into her hushed consultations of women seeking to abort, often underage girls. Cinematographer Arseni Khachaturan frames many of these laterally and askew—the faces off-screen, as Nina does what she must. Sound clenches the overbearing disquiet. She meets girls hit by an unwanted pregnancy, those abused by their step-fathers, assuring them. Standing apart from communally imposed shame and taboo, Nina might be the only kindness they’ll receive. But she’s only met with enveloping hostility on a larger scale.

April moves in enigmatic, stylised cross-currents between the hyper-real and odd, looming restlessness. It doesn’t lend itself to an easy grip but Sukhitashvili’s challenging, elliptical style rewards close attention. What lies beneath Nina’s investment in a solitary life? Where are her friends and family? In her flat, Nina walks around, shell-like. Her interior life demands privacy but also induces curiosity, her unresolved loneliness filling every room. An austere character study, April deeply unsettles till its unyielding close.

April is streaming on Mubi.