Living in an era which is marked by ecological collapse and social fragmentation, ‘Isotropical Futures’, curated by Yash Vikram, brings together practices of Asif Imran, Avni Bansal, David Malaker, Geetanjali Bayan, Harmeet Rattan, Moumita Basak, Sitikanta Samantsinghar, Satadru Sovan, and Unnikrishnan C which are as intimate as they are politically charged.

Through installations, performances, and visual interventions, the exhibition interrogates the illusion of diversity as a panacea for systemic decay. It draws on the scientific principle of isotropy where things seek balance not to advocate for uniformity, but to propose a radical reimagining of collectivity rooted in interdependence, solidarity, and shared vulnerability.

Idea Behind The Theme

Delhi-based Yash Vikram, who is curator of the show, while speaking to 온라인 카지노 사이트 India shared his idea behind bringing together artists from different parts of the country together. “I started with three artists in the show, which the gallery recommended. We sort of worked around nature but when I started working on it, there was so much going on in the world around, like the India-Pakistan issue and so much more. It struck me like the importance of collectiveness and togetherness, solidarity, that can also be a force to reckon with. So the show sort of came together as a way to respond to not only social survival, but also ecological survival,” Vikram said.

Isotropical is a term that's taken from isotropy, it's a term in thermodynamics where if a system is unstable, then all the particles of the system align themselves towards isotropic or a state of equilibrium. Here, Vikram explains that this show broadly is based on this idea and it comes together as a proposition where all the artists have works that sort of reflect on either ecology or differentiation or disparity in the social sense. “And how can both be fought together if we all come together and align ourselves and keep the differences aside.”

Artists’ Show Their Roots, Culture

The walls of Tao Gallery come alive with the stories of nine distinct artists, each weaving a personal narrative through diverse ideas and techniques. Together, their works offer a rich tapestry of roots, culture, and the layered histories of the places they call home.

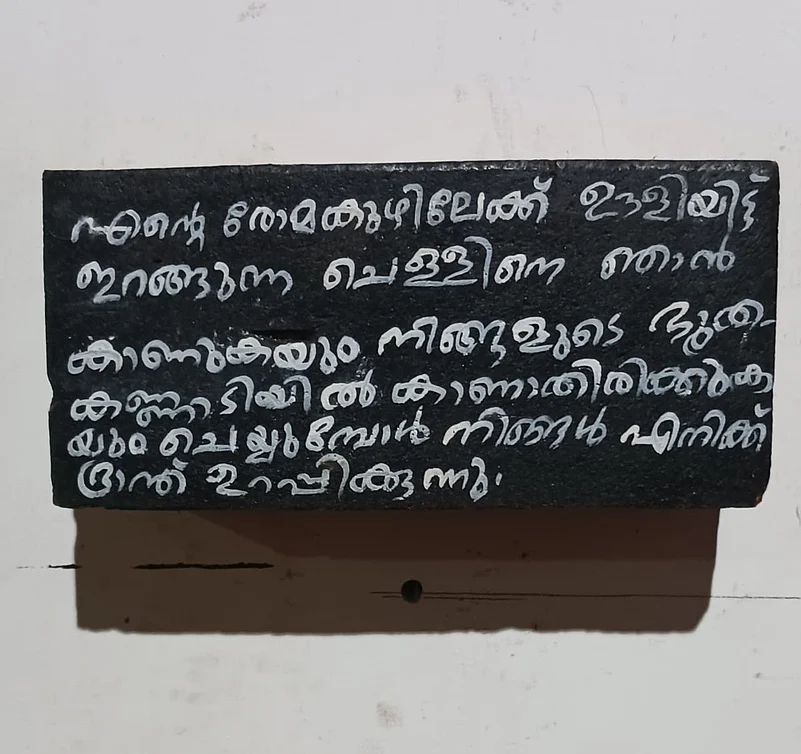

Kerala-based artist Unnikrishnan C grounds his practice in memory, folklore, and indigenous knowledge systems. His works bear witness to the ecological trauma experienced in his native village.

Chandigarh-based artist Avni Bansal interrogates the rituals and beliefs embedded in everyday 온라인카지노 life.

Odisha-based Sitikanta Samantsinghar employs unconventional materials like tea leaves, smoke burns, and neon to craft layered, surreal compositions that speak to rural resistance, displacement, and ecological dissent.

In Vadodara, Geetanjali Bayan draws from traditional crafts such as weaving and crochet, delicately exploring themes of grief, healing, and memory through tactile, intimate forms. Kolkata’s David Malaker works primarily with charcoal and pastel to portray the nocturnal urban landscape.

In New Delhi, Satadru Sovan merges ecological narratives with queer identity through vivid, surreal paintings and performance art, creating a striking dialogue between personal expression and planetary concerns. Bangalore-based Asif Imran investigates the built environment from fading colonial facades to ephemeral street hoardings uncovering the emotional and historical textures of urban life in flux.

Chandigarh-based Harmeet Rattan explains using the medium of light to display the gravity of nature and human connection in his work.

“When the lockdown was announced, there was a kind of collective migration where everyone was on the move in their own way. I was in Delhi at the time, heading back to Punjab. As the restrictions became more severe, I set out for home. On the road, there were no vehicles in sight. I ended up walking nearly 3 to 4 kilometers. The streets were eerily empty, no people, no movement. It was as if the world had come to a standstill.

As I approached my village, I saw it from a distance. The police were already stationed there. What struck me most was the stillness: the only visible signs of life were the lights glowing in the silence. It felt like humanity had vanished. That thought stayed with me: this overwhelming absence of people, this haunting quiet. There were stray dogs, bits of everyday life scattered around, but no human presence. That moment became the foundation for my Desolation series. Even the lights, in their quiet glow, became part of that memory, fragments of what I had witnessed during that surreal time,” Rattan said.

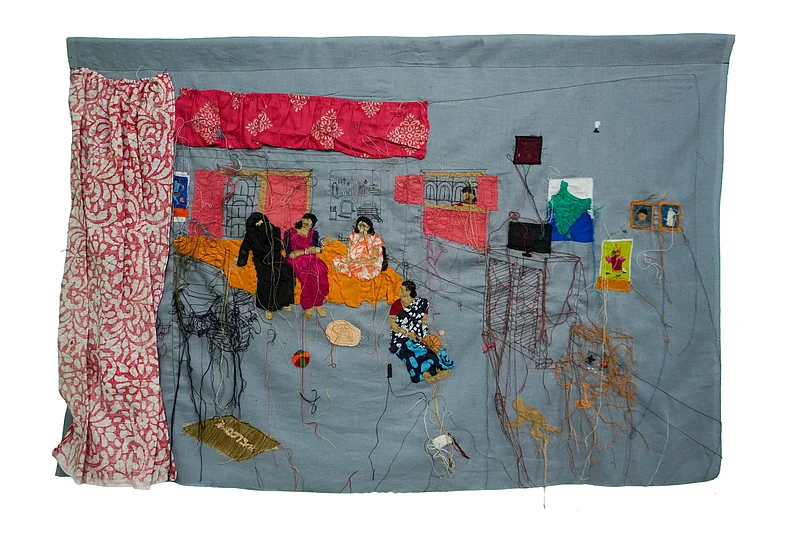

From Bardhaman in West Bengal, Moumita Basak brings together Kantha embroidery, salvaged textiles, and organic materials to examine gender roles, ecological memory, and the complexities of class. She explains that her artistic style is deeply rooted in experiences of women in village life, where everyday their existence was shaped and often reshaped by the realities of conflict.

“I have spent time in villages and in cities and have seen the different realities of women's livelihood and day to day life. This keeps on changing and I make sure that wherever I go, I observe the women of that place, their habits, livelihood and cultural exposure,” Basak said.